The key to building children’s confidence in Maths

/Read on to discover …

Do girls and boys learn Maths differently?

How to help the child who thinks they’re ‘useless at maths’?

In which ways does Dyslexia affect Maths learning?

What can we do to help more girls see the appeal of STEM careers?

“Children often need a teacher’s gentle help to shift their thinking from ‘I can’t do this’ to ‘I can’t do this yet’. They achieve more when they’re subtly encouraged to have a ‘growth mindset’ towards their capacity to solve problems.”

Author

Angela Farley, Head of Mathematics, Sompting Abbotts Preparatory School. Ms Farley is a specialist Maths teacher who holds a First Class Honours degree in Maths & Sports Science and a Masters in Education in Mathematics & Dyslexia. You can read more about Ms Farley’s career and background in her staff profile here.

When I tell people I teach Maths, I often receive incredulous looks. With my taste in clothes and hairstyles, most people assume I’m an Arts or Drama teacher. They’re both passions of mine, but my two natural talents are Maths and Sports.

It’s a pertinent question that should be asked. Why shouldn’t a funky female be a mathematician? Where do our stereotypes come from? Are there gender differences in the world of Maths?

At my all girls’ convent school, doing Double Maths at A-level had me labelled a ‘genius’. I didn’t see my talent though as any greater or lesser than that of other girls in my year. Many could draw exquisitely, sing beautifully or produce amazing paragraphs of descriptive English prose. They’d leave me awestruck!

My brother, close in age to me, was doing the same A-levels at his boys’ grammar school. There, though, being good at Maths wasn't seen as anything ‘special’.

So there was clearly a difference between the thinking about girls and boys. But was this to do with our brain biology, education methods, socialisation, or what?

There are many different thoughts about this. So here I’ll write from a personal experiential perspective.

(However, there are some articles I’ve found interesting on this subject. I’m listing them below for anyone wishing to look. They cover some of the arguments around the findings of brain imaging and applications to education, especially relating to gender.)

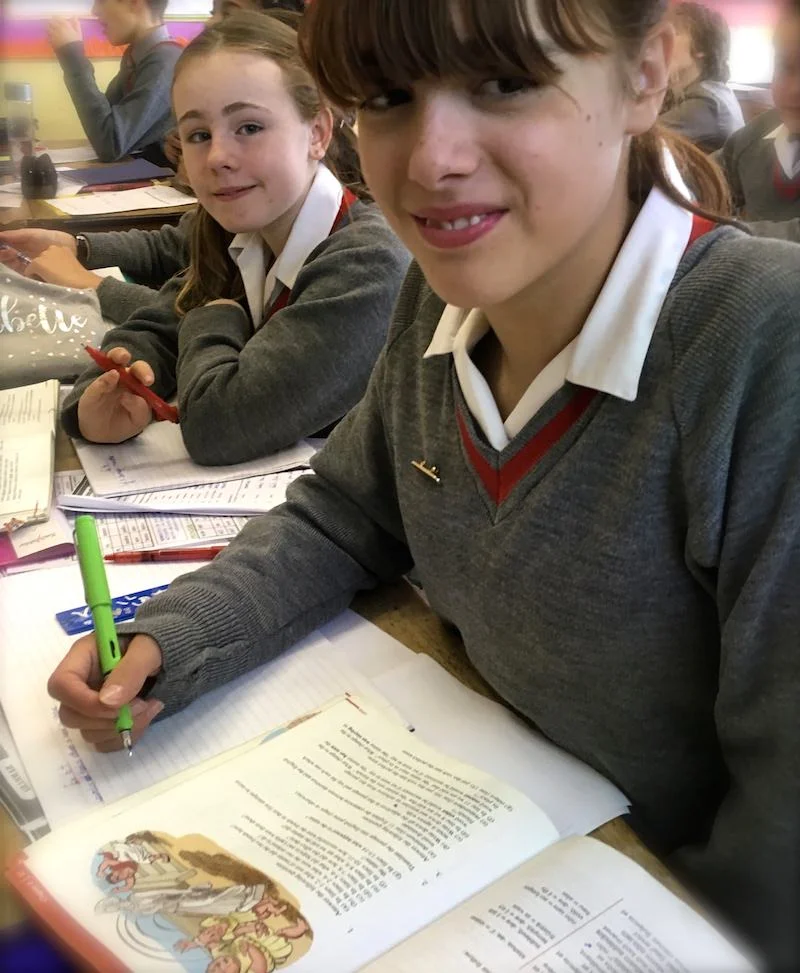

Ms Farley with a Year 6 Mathematics class at Sompting Abbotts

Maths ability is often linked to confidence

I've now been teaching Maths across almost two decades. And I do see a difference between boys and girls and how they learn.

Many boys who are 'on top of Maths' just ‘get it’. As soon as I'm writing on the board, the answer is there. Girls, though, can tend to be less inclined to 'forge ahead'. I’ve seen that unless they’ve got a conviction of full mastery, they often feel they just don't ‘get it'.

The girls frequently need and appreciate a fuller and wider exploration of ideas. Now this is a gross generalisation. I definitely fell into the 'boys’ camp' in my own approach. But in my experience, I’m the exception, rather than the rule.

It’s why I advise GCSE students not to take Maths at A-level unless they love it and/or find it easy. At this level, mathematical concepts start to go 'outside the box'. Creative mathematical thinking is paramount.

Recent changes in the curriculum and assessment have taken Maths GCSE closer to A-level standard. Today, achieving a level 8 or 9 far exceeds the level before required for an A or A*. This new marking criteria means there’s more of a natural selection process.

Boys often have lower levels of anxiety about their Maths and higher levels of confidence in their Math skills even though girls show similar performance levels.

Teaching Maths to the student, not to the Maths test

But it is possible for Maths teachers to nurture every child to achieve his or her best results.

A teaching style that expects a pupil to ‘just get it' is failing many. This can be a fault with both male and female teachers who find Maths easy. But it doesn’t play to everyone’s way of learning.

Children often need help to shift their thinking from ‘I can’t do this’ to ‘I can’t do this yet’. They achieve more when they’re gently encouraged to have a ‘growth mindset’ towards solving Maths problems.

Sadly, in many schools today, there's less curriculum time available and increasing pressure on teachers to achieve exam results.

These factors can mean that more hands-on teaching styles, like experiential learning and more fun and play, get overlooked due to time pressures.

Mathematics and Dyslexia

I’ve always had a special interest in the application of learning to practice. My academic qualifications include a First Class Honours degree in Maths and Sports Science. I also hold a Masters in Education in Mathematics and Dyslexia.

I’ve worked with many Dyslexic students across the years (and those who present closely to this spectrum). Boys tend to be diagnosed with Dyslexia more frequently than girls. What I’ve observed is that they’re often highly creative and brilliant at thinking ‘outside the box’.

For me, Arithmetic is all about numbers and Mathematics is all about theory. Arithmetic is your 'sums'; rather as spelling is to writing. This in my mind can often be taught to a reasonable level.

Maths, by contrast, for me is the ability to grasp concepts and think creatively (in a mathematical sense). This is where I believe mathematical talent lies. Algebra is often seen as being the beginning of this sense of Maths. It’s where we also consider the general rather than just the specific.

At school, we tend to be quite far down the path before we start to develop and assess academic mathematical thinking. If their Arithmetic is poor, youngsters often feel 'rubbish at Maths' when this may well not be true.

Gentle and empathetic teaching helps ensure children don’t feel overwhelmed when learning Maths

Creative mathematical thinking

This is where Dyslexic students can often really struggle and give up. Being young and failing miserably at sums and times tables tests rarely inspires the creative mind.

It takes a special child, and/or specific teaching to suffer through the rigours of Arithmetic to have confidence to realise there are mathematical concepts they could excel in. And vice versa, children who can do sums but who do not have mathematical thinking become very disappointed as they drop their marks in Maths as the concepts becomes more complex.

This is evident in exams where students do better in calculator tests than without. It is often mistakenly thought that having a calculator means the task is easier. Actually, calculator papers require a higher level of thinking and understanding.

I’ve witnessed Dyslexic students struggle to make half marks on non-calculator papers, which are far easier. But then to go on and score 80%+ on calculator papers, by showing excellent thinking and understanding.

At university, I studied under Mathematics tutors who were themselves Dyslexic. They were amazing thinkers but often got their simple sums wrong (soon corrected!).

Did you know there are a large number of high-achieving scientists and mathematicians who were Dyslexics?

Einstein is probably the most famous example. Alexander Graham Bell, Michael Faraday and Galileo are others. I wonder how well Einstein did with his basic sums when young at school? Quite possibly, not very well at all…

Ms Farley giving one-to-one help to a pupil. Research conducted by Accenture of girls aged 12 in the UK and Ireland found that 60% felt that Maths and Science were “too difficult” to learn. The girls thought the subjects were "better suited to boys" because of their brains, hobbies and personalities

Girls and Maths: what’s not adding up?

It’s a shame that many girls don't pursue more mathematical studies or careers because they see it as a male arena.

In the UK, all students have to study Maths until the age of 16. Boys and girls achieve roughly similar GCSE results. But the numbers who go on to study Maths at A-level reveal a dramatic gender split. The most striking gaps are in Physics and Maths. In 2018, girls accounted for only 39% of Maths A levels, 28% of Further Maths A levels, and just 22% of all Physics A levels.

Teachers and parents, however, are now more aware of the need to encourage girls to take Maths and Sciences. It is the only way initiatives to close the gender gap in STEM industries are to succeed.

Currently, women account for only 14.4% of the UK STEM industry, with a knock-on effect on the gender pay gap.

One of the highest international prizes for Mathematics has recently been awarded to a woman. She is Professor Karen Uhlenbeck of the University of Texas in Austin, US. She received the Abel Prize for her work on "minimal surfaces" such as soap bubbles.

By finding ways to unite Geometry and Physics through new mathematical approaches, Professor Uhlenbeck is the first female ever to win the Abel Prize award. Photo credit: https://www.ias.edu/news/press-releases/2019/abel

Careers for Mathematicians

Most of the girls at my school who took Maths and sciences wanted to be doctors or vets. I don't know if my female peers really enjoyed Maths. I know they had to work hard at it. I was aware I found the subject easy in comparison.

I didn’t have any inclination to go into medicine. I took Maths because I found it easy. It meant I could get my homework done fast. Then I was off to enjoy my extra-curricular passions – mostly sports – all the quicker.

My brother wasn't interested in medicine either (although our mum would have loved one of us to be a dentist!). For him, being good at Maths meant better prospects of a well-paid job.

That held no interest for me. I wanted to explore the world, discover different life experiences and play netball for England, which was something that money could not buy.

Careers guidance was poor at my school back then. I had no idea what I could ‘do’ with Maths. One vague idea seemed to entail ‘working in the City’ which had no appeal for me whatsoever. I didn't want to work with robotic men (or women) dealing in stocks and shares.

A modern-day mathematics role model: Abby in NCIS. Image source: Wikipedia

Today, happily, there are much more exciting role models of mathematical women available to girls. I'm a big fan of forensics genius Abby in the TV series NCIS. I also love the super-analytical detective Olivia Benson in the police drama Law and Order: Special Victims Unit.

But I doubt finding a career I cared about would have made me try any harder at Maths. I just loved the subject for itself.

Gender roles and stereotypes

As we continue to develop as a society and to understand what equality of opportunity actually means, there will be more such examples.

I try to encourage all my students to reach their full potential. I will also understand if a female mathematician doesn't feel comfortable in a particularly male setting.

Maybe if I'd been motivated by a high-achieving City job, I’d have taken up work in a sector with few female role models. But, looking back, I suspect I always knew it wasn't worth the damage to my spirit or psyche to have to 'fight' in those arenas.

With my sporting ability and nature, I am highly competitive. My Maths strengths mean I have good logic and problem-solving abilities. So in theory, I could have been a good candidate for a male-dominated field of work.

But in my case, it would seem that my gender and emotional make up resulted in a need to 'care' about my work. I wanted to teach because it was work that ‘meant’ something to me and would make a difference.

I longed to travel and explore exciting life experiences. I went on to play netball for NW England against New Zealand and in Barbados. We were part of a sporting centre of excellence, and I played for the First Team for Surrey when we were top of the national county leagues. When I won my two gold medals for sprinting at the British Masters championships, it ticked a box for me.

Girls relaxing during break in Sompting Abbotts’ grounds

Vive la différence

It's great that we’re all different. For example, I certainly wouldn’t want an emotionally sensitive person performing brain surgery and flinching at the site of blood. A degree of emotional detachment is a great asset for that work.

However, I do believe we are now seeing more female attributes being valued, heard and listened to in the workplace.

I think women – especially the mathematical ones with logic and problem-solving skills – can make great leaders. After all, in general, the female leadership style tends to prioritise cooperation over domination.

Up to now, however, many female leaders seem to have used rather typical male leadership characteristics. Margaret Thatcher was one. She famously replied, when a journalist asked her what was it like to be a woman Prime Minister: "I have no idea, dear, as I have never experienced the alternative."

But many instigators of peace close to home in our time have come from female leadership. That is something to be very proud of. Women, for example, played an important role in the Good Friday Agreement and the Greenham Common Movement.

It's wonderful that at my school both the Maths and Science Departments have female heads. The English and Humanities departments, however, have male heads. How’s that for role models?

Hopefully, at Sompting Abbotts, we’re having a progressive influence!

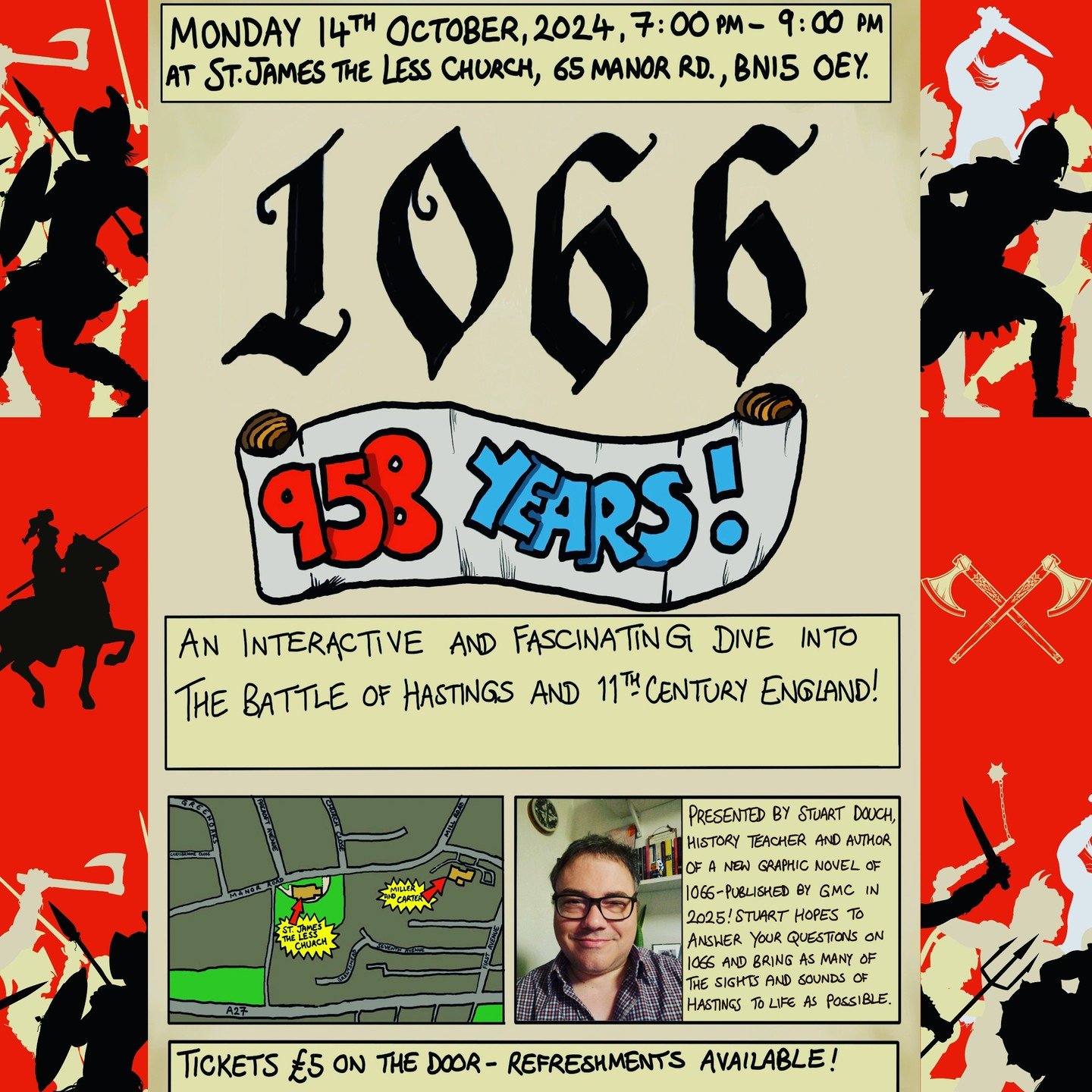

Sompting Abbotts’ Success at the United Kingdom Mathematical Trust Junior Mathematics Challenge

Sompting Abbotts’ pupils have a track record of high performance in the UKMT Junior Mathematics Challenge, the national competition aimed at the highest-achieving children n England.

The Junior Mathematical Olympiad is run by the UK Mathematics Trust, a fantastic organisation that promotes Maths in school by, among other things, organising national competitions.

In 2018, Kiran P and Jonny T (pictured here with Maths Head Ms Farley) both were awarded a Gold, with Jonny T going through to the next level, 'The Kangaroo', in June. Jonny moved to Winchester College in Sept 2018 where he was selected for the Junior Maths Olympiad in his first term there, the highest rung of the UKMT Challenge, placing him in the top 0.37% of children nationally.

In 2019, two further Sompting Abbotts' pupils had great outcomes. Henry G was awarded a Silver, and Rudi B, a Gold. Rudi also went through to The Kangaroo and was awarded Merit, the highest grade possible.

Over 270,000 pupils entered nationwide. Of these, only 6% received Gold and 13% Silver. Extra kudos gpes to Rudi who was among the only 3% invited to sit the Junior Maths Olympiad!

This is an amusing Simpsons episode to watch. It's called 'Girls just want to have sums' (2006). It's set in a fictional school in which the boys and girls are taught separately. The teaching of Maths is completely different for each sex. The girls sit in a pink, fluffy room and the teacher tells them: “Problems? That’s how men see Maths. Something to be ‘figured out’”. The boys sit in a sparse classroom before a blackboard showing a complicated problem involving formulae to work out the volume of composite spheres. Although this is far from an accurate picture of single sex education, it does highlight some interesting points!

Further reading

All views expressed in this article are the author’s own.